Text this colour is a link for Members only. Support us by becoming a Member for only £3 a month by joining our 'Buy Me A Coffee page'; Membership gives you access to all content and removes ads.

Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland 1868 Pages 40-46 is in Journal of the Historical and Archaeological Association of Ireland 1868.

Remarks on a Class of Cromleacs for which is the name "Primary," or "Earth-Fast," is Proposed" by George V. du Noyer, M.R.I.A., District Officer, H. M. Geological Survey of Ireland.

In my "Remarks on a Kistvaen and some Carvings on an 'Earth-fast' rock, County of Louth," published in our "Journal," vol. v., second series, p. 499, I observed "more over, I believe I can show that we possess two distinct varieties of cromleac." The object of the present Paper is to illustrate and explain this remark.

In inductive reasoning, we must assume something at starting. Thus, I have given the name "primary" to that peculiar kind of cromleac, which consists of one large slab or block, one end or side of which rests on the ground, the other being raised from it, and supported in a slanting position by one or more smaller blocks.

I do not adopt the name "primary" for this peculiar class of megalithic structures in a chronological sense, as such would be incapable of proof; but I do so on the theory of progressive structural development, which na turally suggests, that the more simple the structure or form, the more remote its age; and those who have studied the megalithic structures of our own Island and of western Europe admit that they are not all of one period, though they are most probably the works of one race.

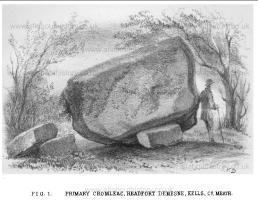

In the summer of 1866, I found, in the demesne of Headfort, at Kells, Co. Meath, a large subangular block of grey silurian grit, measuring 9' 6" + 6' 0" + 8' 8", the southern side of which rests on the ground, while the northern is tilted up, and is supported on a single, small, and somewhat angular block of the same material (see Plate facing this page, fig. 1). At first the true character of this structure was not apparent to me, and I described it in my paper on the Waterford cromleacs as an example of an unfinished and abandoned cromleac. Subsequent examination into this subject led me to abandon this idea, and I am now convinced that the Headfort cromleac is a most interesting example of a hitherto unrecognized class of such remains, and I therefore place it first in the illustration and description of "primary" or " earth-fast" cromleacs.

On applying to the Marquis of Headfort, his Lordship communicated to me the following particulars regarding this cromleac:

"The only information I can give you is as follows: the large block of rock to which you allude was originally covered up, but not in a tumulus, to the best of my knowledge. When the approach to the house was made, about 120 years ago, the ground was levelled, which concealed this large rock. The soil is of a gravelly nature, and an old gravel pit lies within a few yards of this rock. I believe there is not a person now alive in Kells, or its vicinity, who can throw any further light upon this subject. No bones or relcis of any kind have ever been found above or near this stone."

From the foregoing, it would appear that this cromleac was originally enveloped in sand and gravel — an apparent fact which I have much pleasure in handing over to the consideration of those antiquaries of the Danish school, who hold that all cromleacs, or "dolmens" were once thus covered up and concealed.

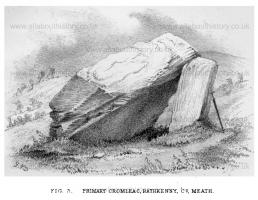

The next illustration (see Plate facing p. 42, fig. 3) represents the "primary" or "earth-fast" cromleac of Rathkenny, Co. Meath [Druids Altar aka Rathkenny Portal Tomb [Map]]. Its general similarity to that at Headfort is at once apparent, but it is a far finer example of rude constructive skill. The inclined slab measures 10' 10" + 8' 6” + 3' 0," it slopes to the N.N.E. at an angle of 37° to the horizon, and rests against an angular undressed block of grit, measuring four feet above the ground, and 2 + 1' 6" at its sides.

The upper surface of the large stone is profusely covered with small cup-shaped hollows, some of which may be natural, and due to unequal weathering away of the calcareous portion of the grit; but many of them are certainly artificial.

Near the lower edge of this slab, and over the space between the cup-hollows, there are numerous scraped oghamic looking "graffiti," many of which are somewhat similar in character to those markings on the "earth-fast" rock at Ryefield, Co. Cavan, which I have already figured and described in our "Journal." The under surface of this stone is ornamented near its N. W. angle by a group of seven small circles, produced by rude punchings; the largest measures nine inches, and the smallest four and a half inches in diameter. The supporting stone of this cromleac is similarly decorated on its inner face by another group of semicircles, equal in size, but differently arranged to the former. My friend, Mr. Eugene Conwell, has described this singularly interesting "earth-fast" cromleac, and fully illustrated it from my sketches in the "Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy;" vol. ix. p. 541; and he has there expressed his conviction, that this remain was never more perfect than as we now see it — an idea in which I fully concur.

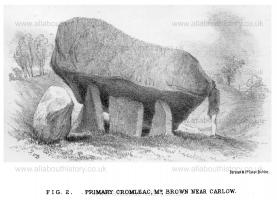

The third example of this class of cromleacs is that at Mount Brown [Mount Brown aka Bronshill aka Kernanstown Dolmen [Map]], within one mile and a half of Carlow (see Plate, facing p. 40, fig. 3). This magnificent block of granite measures 22’ 10” +18’ 9” 4-4" 6” and is inclined at an angle of about 35° to the horizon, being supported most securely on three upright blocks of granite of unequal height, whereby the top stone is made to incline in such a way as to rest on the ground at only one angle.

For another example of these cromleacs I would refer to a Paper by the Rev. James Graves, "Journal" (vol. i. first series, p. 130), in which he describes and figures an "earth fast" structure of the class now under consideration, near Jerpoint Abbey, in the county of Kilkenny, called Clough-na-gower.

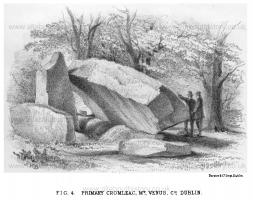

The last illustration is that of the so-called ruined cromleac at Mount Venus, county Dublin [Mount Venus Burial Mound [Map]], (see Plate facing this page, fig. 4). Beyond a question this remain is a genuine "primary," or "earth-fast" cromleac, and is as fine an example of its type as we possess in Ireland. The two enormous blocks forming it are of granite, the larger inclined stone being about 18’ + 8’ + 4’; the upright stone against which it rests being about eight feet above the ground, and over three feet square. I regret I have not the exact measurements of those blocks; but these given are not very far astray.

In point of construction, this cromleac very closely resembles that at Rathkenny, as will be apparent by reference to the illustrations.

There are many other examples of this kind of cromleac in Ireland, but their true character has invariably been overlooked, and they have all been regarded as ruined cromleacs of the normal type.

Amongst our "earth-fast" cromleacs must be classed that at Ballylowra, in the parish of Jerpoint Church, figured and described by the Rev. James Graves, in our "Journal," (vol. i., first series, p. 130). The writer states that the covering stone rests in a sloping position against three of the upright stones on which it had been originally poised; the covering stone measures 12” + 8’ 6” + 3”, the highest part of it being now1 nine feet from the ground. That this remain was ever a true cromleac of the normal type is by no means certain ; though it is not impossible that such might have been the fact.

It is, of course, quite possible, that the covering stone of a cromleac of the fully developed type, might, under certain circumstances, slip from off its supports ; most pro- bably those smaller stones at its depressed end would be the first to give way, as they received the excess of weight of the covering stone. I cannot help thinking, however, that when this event took place, the causes and forces which first induced the shaky condition of the entire fabric would have so weakened it throughout, that the supporting stones against which the enormous covering block grated in its fall from mid-air, would have been crushed, or at least overthrown in the general ruin, and the whole fabric would have fallen, prone, like a house built of cards.

Such an event as I have supposed is well exemplified by studying the condition of the really ruined cromleac, on the south bank of the Glen of the Potter's river, near the road to Arklow, Co. Wicklow, which I have figured and described in my "Antiquarian Sketches," inthe Library of the Royal Irish Academy. This cromleac was erected on the sloping bank of the river, and the rain of ages gradually washed away the earth in which the upright supporting stones had been sunk, till at last they became undermined, and were no longer able to bear the weight of the large block resting on them ; the whole structure then fell to the earth, a mass of mindless ruin. Not so with reference to the "earth-fast" cromleacs, such as I have illustrated; their so-called ruins are, on the contrary, full of preconceived design ; they embody an intention, rude though it is, in conception and execution.

I admit that if we had but one example of what I call a "primary," or "earth-fast" cromleac, it would be hazardous to form a theory from it; but when we have numerous objects of this class, it requires but a little consideration and exercise of reasonable imagination to perceive that we are dealing with a class of objects in themselves perfect.

I confidently assert, that in the example of "primary," or "earth-fast" cromleacs, which I now illustrate, there is not the least evidence for the supposition that any of them had been originally constructed after the fashion of what we may call the normal cromleac; on the contrary, it is very evident that they are now as perfect as they were ever intended to be — minus the effects of atmospheric action.

"Primary," or "earth-fast" cromleacs, are found in Scotland and Wales ; in the former, the finest and most remarkable example in existence is that at Bonnington Mains, Mid Lothian, figured and described by Professor Wilson, in his admirable work on the "Prehistoric Remains of Scotland," vol. i., p. 26. This enormous rounded boulder rests at an angle of, possibly, 50° on a single supporting stone of about six feet in height above the ground, and at a point distant from its raised end about one-third of its entire length. This structure was never different in form to what it is at present, and is not a ruined cromleac, as has been supposed.

In the "Archæologia Cambrensis" for January, 1867, p. 62, Mr. Owen describes and illustrates a cromleac at Llandegni, as an example of a ruined cromleac. This remain, on the contrary, belongs to the class of structure I am describing: it consists of a single large tabular slab, raised and supported, at one end only, by two small blocks, placed as far apart as possible, and, therefore, close to the outer ends of the inclined slab. If this table-stone was ever poised in air, like an ordinary cromleac, the loftier supporting stone must have fallen, and been most carefully removed; and, even thus, its altitude from the ground would have been so trifling as to have rendered it quite unlike any structure of its class.

In my Paper on the Waterford cromleacs, already alluded to, I directed attention to an example of what I, called an unfinished and abandoned cromleac on the side of the glen, just below Ballyphilip Bridge; such was my idea on this subject at the time: but further insight into the matter has caused me to alter it. This remain is an example of a "primary, or 'earth-fast' cromleac."

Note 1. This cromleac unfortunately no longer exists, having been broken up and removed some years ago by the occupier of the land. — Ed.

In the month of March, 1867, after I had this Paper in nearly its present form, I forwarded to Col. Forbes Leslie proof impressions of the lithographs which illustrate it. From his reply I select the following passage:—

"On examining your lithographs of 'primary cromleacs,' an idea occurred to me, that they never have been, and never were intended to be altogether supported by stones, but that one side or end was intended to rest on the ground; and these would well deserve the name of 'primary cromleac,’ as you suggest, their prototype having been the natural altars — 'earth-fast stones' — which were, until lately, perhaps in some cases till are regarded with veneration, In case you may not have Borlase’s Cornwall at hand, I send you a sketch, taken from that work, of one of these natural altars. I recollect that the great Dolmen, on the plain near Loc-maria-ker, in Britany, has one side resting on the ground."

It is gratifying to find so accomplished an author and accurate an observer of Celtic remains agreeing to, and corroborating the ideas which I had formed on the subject of "primary," or "earth-fast" cromleacs; and I have every reason to hope that the theory will stand the test of future criticism. In all I have written with reference to our cromleacs, I have but one object in view, that of arriving at some definite truth regarding them; and if my ideas on this subject are not correct, I shall be the first to abandon them.

I now leave the subject of "primary" or "earth-fast" cromleacs, to be more fully examined into by those who have more leisure, and a better opportunity of studying it than I can have, recording my belief, that these remains merit a more careful examination than has yet been given to them under the impression that they are but ruined cromleacs of the normal type, whereas they are a distinct class of Megalithic structures, and possibly indicate the very earliest efforts at positive construction, attempted by the erectors of the "menhirs" and "dolmens" of the continent, and the "gallauns" and "cromleacs" of the British Islands.

Weights of the top stones of the following cromleacs:—

Headfort .... 14 tons.

Rathkenny .... 19

Ballyphilip .... 12

Mount Brown .... 110

Knockeen .... 10½

Gaulstown .... 6

Ballynageeragh, . . . 6¾

The weight of the first four has been determined by W. S. W. Westropp, Esq., and that of the last three by James Budd, Esq. It will be perceived that the top stones of the "primary" cromleacs are much heavier than those of the normal class.