Text this colour is a link for Members only. Support us by becoming a Member for only £3 a month by joining our 'Buy Me A Coffee page'; Membership gives you access to all content and removes ads.

Text this colour links to Pages. Text this colour links to Family Trees. Place the mouse over images to see a larger image. Click on paintings to see the painter's Biography Page. Mouse over links for a preview. Move the mouse off the painting or link to close the popup.

All About History Books

The Deeds of King Henry V, or in Latin Henrici Quinti, Angliæ Regis, Gesta, is a first-hand account of the Agincourt Campaign, and subsequent events to his death in 1422. The author of the first part was a Chaplain in King Henry's retinue who was present from King Henry's departure at Southampton in 1415, at the siege of Harfleur, the battle of Agincourt, and the celebrations on King Henry's return to London. The second part, by another writer, relates the events that took place including the negotiations at Troye, Henry's marriage and his death in 1422.

Available at Amazon as eBook or Paperback.

Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Volume 26 1903 is in Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

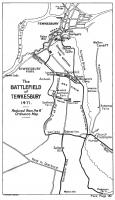

The Battle Of Tewkesbury, [4th May] 1471. By Rev. Canon Bazeley, M.A.

AT daybreak on Easter Day, April 14th, 1471, a fierce battle commenced at Barnet between Edward IV. and Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick.

At first the Lancastrians had the advantage; but an accidental collision between two parts of Warwick's forces, which occurred in consequence of a thick fog, changed the fortune of the day. By noon Warwick the King maker, his brother, the Marquis of Montague, many other leaders on either side, and some four thousand1 of the rank and file lay dead or dying on the blood-stained field.

The same day, or it may be on the preceding day, Margaret of Anjou, Henry VI's Queen, landed at Weymouth after many futile attempts to cross the wind-swept Channel. With her were Edward, the young Prince of Wales, John Longstrother, Prior of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem, Lord Wenlock, and many other adherents.

Note 1. Green's Hist. of the English People, ii. 45.

Hall, Grafton and other chroniclers tell us that she proceeded to Beaulieu Abbey, in the New Forest, but this is evidently a mistake. An unknown chronicler, who calls himself a servante of "Edward the Fourth" and claims to have been an eye-witness of the events he relates, tells us that Margaret took up her quarters at Cerne Abbey [Map], in Dorset1. It was the Countess of Warwick, who had landed a few days sooner, at Portsmouth, who had taken sanctuary at Beaulieu.

Note 1. Fleetwood's MS., printed by the Camden Society as their first volume, and entitled Historie of the arrival of Edward IV. in England and the finall Recoucrye of his Kingdomes from Henry VI., A.D. 1471.

The evil news from Barnet reached Margaret on Easter Monday, and for a time her dauntless courage forsook her. "When," says Hall, "she harde all these miserable chaunces and misfortunes, so sudainly one in another necke to have taken effect, she like a woman all dismaied for feare, fell to the ground, her harte was pierced with sorrowe, her speech was in a manner passed and all ler spirits were tormented with melancholy."

But the Duke of Somerset and the Earl of Devon, who hastened to her at Cerne, encouraged her to try once more the chances of a battle, The former, Edmund Beaufort, who was destined to wreck her cause a few weeks later at Tewkesbury, was the second son of Edmund, Duke of Somerset, and grandson of John of Gaunt. His father had fallen in the battle of St. Alban's in 1455, and his eldest brother, whom he succeeded, had been beheaded at Hexham in 1463. His mother was Alianore Beauchamp, one of the colheiresses of the mighty house of Warwick. Thomas Courtenay, Earl of Devon, had been present with his father at the battle of Towton in 1461, and had been attainted by Edward IV.

Acting on the advice of these nobles, Margaret and Prince Edward removed to Exeter, and sent for Sir John Arundel of Lanherne and Sir Hugh Courtenay of Bocon- nock, Cornishmen of considerable influence: and renown. The presence of the Queen in the capital of the West, and the support of the principal nobility. and gentry of those parts, quickly availed in attracting to her standard a large force, and by the end of April she was ready to march northwards.

In the meanwhile Edward IV., who had disbanded his victorious forces after the battle of Barnet, having knowledge of ler proceedings, was raising a new army in London. On April 19th he went to Windsor, where he kept the Feast of St. George (April 23rd), and on the day following he set forth to meet his foes.

It was the intention of Queen Margaret to cross the Severn at Gloucester and join forces with Jasper Tudor, Earl of Pembroke; but she strove by false reports to lead her foe to suppose that she would march through the southern counties to London, hoping by this stratagem to elude his army.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Jasper Tudor, whose chequered career is full of interest and romance, was the second son of a Welsh knight, Sir Owen Tudor, and of his wife, Queen Katherine, widow of Henry V. Their elder son, Edmund of Hadham, who married Margaret, daughter of John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, became the father of Henry VII. Jasper Tudor was created Earl of Pembroke by his half-brother, Henry VI.; but in 1461 he was compelled to fly from the kingdom, and the earldom was granted to William Herbert. In 1470, on the capture and execution of Herbert after the battle of Edgecott, Jasper Tudor was restored to his earldom and made guardian of his nephew, Henry Tudor, then a boy of ten years old. In 1471 he raised troops in Pembrokeshire and marched eastwards on the north bank of the Severn to join forces with Queen Margaret; but, as we shall see, the refusal of the citizens of Gloucester to allow Margaret to cross their bridge, and the decisive battle of Tewkesbury, changed his plans and frustrated his hopes. “He retired to Chepstow Castle, where he ran the risk of being captured by Roger Vaughan, an emissary of Edward IV. Later on he was besieged in Pembroke Castle, but he managed to escape to Tenby and took ship for France with his nephew. For fourteen years they were poverty-stricken exiles, and well-nigh prisoners, in Brittany. In 1485 they landed at Milford Haven, and the battle of Bosworth Field which quickly followed placed Henry on the throne. Jasper for the third time became Earl of Pembroke, and was restored to his honours and possessions. He married Katharine Woodville, sister of Elizabeth, Queen of Edward IV. and widow of Henry Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, and he died on the 21st of December, 1493, leaving no issue.

Edward spent Sunday, April 28th, at Abingdon, and on the day following reached Cirencester by the Ikenild Street. There tidings reached him that the Queen would be at Bath on Tuesday, the 30th, which was true, and that she would advance on the morrow to give him battle, which she had no intention of doing. However, on Tuesday Edward set his forces in array and marched three miles out of the town1, no doubt occupying the Roman camp known as Trewsbury, which commanded Ackman Street2 and the source of the Thames.

Note 1. "For whiche cawse, and for that he would se and set his people in array, he drove all the people owt of the towne, and lodgyd hym, and his hoste that nyght in the fielde iij myle out of the towne." History of the Arrival of Edward IV

Note 2. The name given to that part of the Foss-way connecting Cirencester with Bath.

It does not appear why he forced the male inhabitants of Cirencester to accompany him to Trewsbury. Perhaps he doubted their loyalty, and he did not wish in case of a repulse to have a hostile population in his rear. He had practised the same strategy before the battle of Barnet: Edward "wolde ne suffre one man to abyde in the same towne, but had them all to the field with hym1."

Note 1. Fleetwood's Chronicler, pp. 18, 25.

On Wednesday, the 1st [May 1471], seeing no sign of the enemy's approach, Edward proceeded to Malmesbury, to find that the Lancastrian army had turned aside and occupied Bristol. This ancient borough, which at that time ranked next to London in wealth and population, was divided in its sympathies, but the Queen obtained the provisions she greatly needed, as well as money, men and artillery1; and on Thursday, May 2nd, she marched by the Patchway and Ridgeway to Berkeley Castle, where she rested that night.

Note 1. As we shall see, Harvey, the Recorder of Bristol, was one of those who died for the Lancastrian cause at Tewkesbury.

Smythe, the Berkeley historian, tells us nothing in his Lives of the Bevkeleys of this visit, nor do we know where William, Lord Berkeley, was at this time. He had been carrying on a civil war on his own account, and on the 20th March, 1470, he had fought a pitched battle at Nibley Green, against Thomas Talbot, Lord Lisle, and had slain him.

Edward IV. crossing the Cotteswolds by. Easton Gray, Great Sherston, and Badminton, occupied the Roman camp of Sodbury, not far from Dyrham, where the British kings of Gloucester, Cirencester and Bath had sustained a crushing defeat from the Saxon invaders in 577.

A skirmish between the advanced guards of the two armies seems to have taken place in the town of Chipping Sodbury [Map]. On Friday morning, May 3rd [1471], Edward learned that his foes had taken their way towards Gloucester; and immediately he sent off a message to the governor, Richard Beauchamp (age 36), son and heir of Sir John (age 62), Lord Beauchamp of Powick, to hold the city for him at any cost and prevent the Queen from crossing the Severn by the West Gate bridge.

Lord Beauchamp was Lord Treasurer of England and Justice of South Wales, and Henry VI had given him an annuity of £60 a year out of the fee farm of Gloucester. He died in 14751. Sir Richard Beauchamp married Elizabeth (age 36), daughter of Sir Humphrey Stafford, and left three daughters coheiresses2.

Note 1. Most sources have Richard Beauchamp 2nd Baron Beauchamp Powick dying in 1503.

Note 2. The daughters were Elizabeth Beauchamp Baroness Willoughby of Broke (age 3), Anne Beauchamp and Margaret Beauchamp. A 1504 Inquisition Post Mortem named three daughters - Elizabeth and Anne as above, and Eleanor, age 26 and more, wife of Richard Rede, with no mention of Margaret.

Queen Margaret having marched all night along the western trackway, arrived at the South Gate of Gloucester at ten o'clock on Friday morning, hoping to be allowed to pass through the city and cross the Severn; but notwithstanding the fact that many of the citizens were well disposed towards her, she was refused admission. At first the Lancastrians threatened to storm the walls, but knowing that Edward was close on their right flank they deemed prudence the better part of valour, and passing through the open lands of Tredworth and crossing the Portway which led to the East Gate, they rejoined the highway beyond the Lower North Gate. One hundred and seventy-two years later another English sovereign, also marching from Bristol and Berkeley, demanded admission, and he also was refused. In Margarets case the refusal brought about disaster on the next day. Disaster followed quite as surely in the case of King Charles, but the end was longer delayed.

The only bridge over the Severn between Gloucester and Worcester was at Upton-on-Severn [Map]. Probably Margaret hoped that by hurrying forward she might outstrip ler pursuers and cross in safety at Upton. There were three roads connecting Gloucester with Tewkesbury in the fifteenth century. (1) The Lower Way, which turned off from the present high-road at Norton in the direction of Wainlode, and passing through Apperley and Deerhurst, kept close to the banks of the Severn as far as. the Lower Lode near Tewkesbury. At its best this was only a trackway for pack horses and mules. It was subject to frequent floods, and often quite impassable. (2) The Upper Way, which followed the course of the present road through Twigworth, Norton, the Leigh, to Deerhurst Walton. Bennett, in his History of Tewkesbury, thinks that from Walton it wound round towards Notclifle, keeping to the lower ground, and crossed Hoo Lane about a quarter of a mile to the west of the Odessa Inn on the present road1. But the name Salter's Hill, which we find on the ordnance map, and which evidently refers to an ancient saltway, suggests that a road climbed the rising ground in a northward direction. From Hoo Lane, where it met a cross-road from Tredington, the Gloucester road ran through Southwick, crossing a little brook2 at the farm, and keeping to the west of what is now Southwick Park. A green way marks its course as far as Lincoln Green. At Lincoln Green it met an ancient British road, which probably connected the Rudgeway3 with the Lower Lode.

Note 1. P. 277.

Note 2. The name of this brook, which played an important part in the battle of Tewkesbury, is unknown; but "Lincoln Green" over which it flows suggests "Coln," and I shall venture to call it so.

Note 3. The Rudgeway was an important British trackway which ran from the mouth of the Tyne across Britain into South Wales. It entered Gloucestershire near Ashton-on-the-Hill, and ran through Beckford and Ashchurch to Tredington, where it crossed the Swillgate by a lode or a bridge. Mr. Witts, in his Arch. Handbook of Glos., suggests that a branch of it crossed the Severn near Tewkesbury, This branch probably crossed the Swillgate at a lode near Prest's Bridge, and ran westward to the Lower Lode.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

It seems doubtful whether, in the fifteenth century, there was any bridge over the Swillgate near the Hermitage1 or any highway leading into Tewkesbury, where the present road enters it, for the abbey property extended from the abbey to the Ham. Some sixty years after the Dissolution, in 1602, a wooden bridge was thrown over the brook; this was rebuilt in 1635 and widened in 1757, and again in 1827, when the causeway leading to it from the town was considerably raised2. It seems probable that previous to 1602 the road from Gloucester turned to the right at Lincoln Green, joined the Cheltenham and Tewkesbury Road at Queen Margaret's Camp, and passing round Holme Castle and below Perry Hill, crossed the Swillgate by a wooden bridge and entered the town by Gander Lane northward of the abbey precincts. This accounts for the position of Holme Castle, It was built to command the only entrance into Tewkesbury from the south. The site of the present Lower Lode Lane probably lay under water, and the traveller on crossing the ode had to climb the high ground where "Tewkesbury Park" now stands. Ancient roads seem to have avoided towns where it was possible, no doubt with a view to escape the tolls which were levied by townsmen on merchandise passing through. (3) There was a third road from Gloucester to Tewkesbury, which was used by Henry VIII. and his Queen, Anne Boleyn, in their progress of 1535. An old book of ordinances in the possession of the Gloucester Corporation tells us how the mayor, sheriffs, aldermen, burgesses and clergy of Gloucester met the royal party at Brickhampton3. This road branched off from the Ermine Street at Wotton, and, crossing Elm Bridge, followed the present Cheltenham road beyond Brickhampton, whence it turned northward, and passing through Staverton, Boddington, and Hardwick Farm, joined the Cheltenham and Tewkesbury road at Tredington Bridge.

Note 1. The Hermitage gave its name to the turnpike erected in the eighteenth century near the present workhouse. Was it the very spot where Theocus built his anchorite's cell late in the seventh century? Leland says, "Theocus Heremita mansiunculam habuit prope Sabrinam unde & Theokesbyria."

Note 2. Bennett, p. 292.

Note 3. See Report of Hist. MS. Depart., No. 12.

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Queen Margaret probably chose the Upper Way, as it led to-the Lower Lode.

Fleetwood's Chronicler tells us that the Lancastrians travelled thirty-six long miles (from Berkeley to Tewkesbury) in a foul country all in lanes and stony ways, betwixt woods, without any refreshment, and that they reached Tewkesbury about four o'clock in the afternoon. Nor were they permitted to march unmolested. Sir Richard Beauchamp attacked their rear and captured several guns, a loss which they felt severely on the next day1.

Note 1. Hall's Chronicle, fol. 31.

Early on Friday morning Edward IV, having divided his army into three forces, and sending on before him his "foryders and scorers", marched thirty miles from Sodbury to Cheltenham by the Portway, along the open table-land of the Cotteswolds, almost within sight of the Lancastrians.

Although it was still spring the weather was very hot, and there was no "mansmete nor lhorsemete", nor as much as drink for the horses. The only stream they crossed on their way, the Froom in the Stroud Valley, was so befouled by the feet of the horses and the wheels of the carriages that its water was unfit for drinking purposes. But the Yorkist host pressed onwards and upwards, and passing the ancient village of Painswick and Kimsbury Camp, they left the Portway at the Abbot of St. Peter's manor-house of Prinknash and reached Cheltenham by Birdlip and Leckhampton. Here they rested for awhile and ate and drank the scanty provisions which Edward had brought with him. Then Edward marched on through Swindon and Stoke Orchard, and spent the night at the old Parsonage House at Tredington, some three miles distant from Queen Margarets position. The churches of these three villages all date from the revival of church building early in the twelfth century, some three hundred and fifty years before Edward marched past them. Edward and his host saw them much as they appear to us now. The house where Edward slept might have been still standing in all its early fifteenth-century beauty; but reckless restorers have swept part of it away, within the memory of man, and have turned the remainder into humble cottages.

Even in these days of steam rollers and macadamised high-roads such marches as those made by the Yorkists and Lancastrians on that 3rd of May, 1471, would be looked upon as worthy feats; but when we consider the terrible condition of the king's highways in the Middle Ages1 and the deficiencies in commissariat arrangements, we are filled with admiration for our countrymen and their leaders.

Note 1. The Road Act of 1722 speaks of the Tewkesbury roads as being even then ruinous and almost impassable.

There is a tradition that Queen Margaret slept at Olepen on her way to Tewkesbury, but it can have no foundation. It probably arose from the fact that an interesting letter from Prince Edward, dated Weymouth, April 13th, and summoning John Daunt to his aid, is preserved at Olepen Manor-house. But as the Daunts only came into possession of Olepen a hundred years after these events, by marriage with the heiress of the Oulepennes, it is evident that the letter was addressed to John Daunt at some other home, perhaps at Wotton-under-Edge, where they were settled in the tenth century.

Fleetwood's MS. tells us that "they pight them in a fielde (i.e. pitched their camp) in a close even at the towne's ende; the towne and abbey at theyre backs; afore them and upon every hand of them fowle lanes and depe dikes, and many hedges, with hills and valleys, a right evill place to approche as coulde well have bene devysed1.

Note 1. Fleetwood's Chronicler, p. 28.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

They had the choice of (1) selecting the strongest position they could find on the Gloucester and Tewkesbury road, and fortifying it as well as they could with the time and means at their disposal; (2) attempting to cross the Severn at the Lower or Upper Lode; or (3) crossing the Avon by the bridge which spanned both branches a little below the parting, and a little above the junction of one branch with the Severn.

The real reason why they adopted the first plan seems to have been that their men were utterly worn out, after a long day's march, and refused to go any further. But it would have been a perilous attempt, and one which would have exposed the rear of the army to destruction, to cross a broad river like the Severn by a ford or a ferry, with a powerful foe close upon them. Again, had they marched through Tewkesbury, crossed the Avon by the ancient bridge and taken up their position on the Mythe, they would have given Edward possession of the town; and he would, by crossing the Lower Lode, have been enabled to intercept the men and supplies that Jasper Tudor was bringing to the Queen. It seems very probable that, in these circumstances, the Lancastrians made the wisest choice in occupying a position which had many natural advantages, and which Edward would have found very difficult to storm had his foes remained on the defensive. Morcover, if they were driven back they could retire to a still stronger position within the town across the Swillgate.

In order that we may be able to picture to our minds the battle-field of Tewkesbury, we must strike out from the ordnance map all the present high-road from the Odessa Inn, at the second milestone from Tewkesbury, to the lodge of the Tewkesbury Workhouse. This part, which runs through the centre of the Lancastrian position near Gupshill, certainly did not exist when the battle was fought. The words of the chronicler, "In a close even at the towne's ende," can only mean in the large field, then undivided, called the Gastons, which extended from the Vineyards on the south of Holme Castle to the cross-road in front of Gupshill and "Queen Margaret's Camp". The Lancastrians faced due south, with this road, deeply cut and in many places defended by high banks in front of them, the Swillgate on their left, and the Coln on their right. They thus commanded the road to Tewkesbury, and could attack in flank a foe attempting to seize the Lower Lode. Swillgate on their left, and the Coln on their right. They thus commanded the road to Tewkesbury, and could attack in flank a foe attempting to seize the Lower Lode.

The chronicler speaks of their "filde" as "strongly . in a marvaylows strong grownd pyght, full difficult to be assayled.

The small five-sided enclosure, about thirty-five yards across, with a ditch and mound, which has been for a long time known as Queen Margaret's Camp, would have been useless as part of the defence of the Lancastrian position. It would have been a death-trap for the defenders in case the outworks were taken. It may, however, have been an outpost of Holme Castle constructed in early times, or it may simply be a memorial of the battle where most of the Lancastrians fell and were buried. An investigation with spade and crow-bar might possibly throw light on its origin; and permission has been obtained.

The Lancastrians, when they took up this position on the evening of the 3rd of May, 1471, were too fatigued to do much in adding artificially to its natural strength; but it would have been folly indeed not to have constructed, however hastily, across the ridge—the most assailable point—a ditch, bank, and high stockade.

This done, they were drawn up in line facing the advancing foe. The Duke of Somerset and his brother, Lord John Beaufort, who, commanding the "vawarde", would naturally be stationed on the right, and hold the ground which lay between Gupshill and Lincoln Green. Prince Edward, son of Henry VI, the Prior of St. John, and Lord Wenlock, who commanded the centre, would occupy the ridge, and would protect the Queen, who probably slept (if gentle sleep visited her at all that night) at Gupshill Farm.

The half-timbered part of this interesting dwelling is certainly as old as 1471. Two seventeenth century gables bear the initials F.I, a fleur de lys and the date 1665. Windows of a comparatively modern style were inserted during the eighteenth century. The house is now divided into several tenements. The estate was held of the Earl of Gloucester in the time of Edward I by a family called Conquest, and was described as Gopishull, within the Manor of Tewkesbury. In the reign of Charles I it was held by Ralph Cotton.

The Earl of Devon had charge of the rearward, which formed the left wing and extended as far as the Swillgate, commanding the high-road from Tredington to Tewkesbury.

Note. Barrett, in his account of the battle, misled by his ignorance of the cross-road, is forced to reverse the usual military practice of the Middle Ages and place Somerset on the Lancastrian left. As will be seen, this involves him in many difficulties.

On Saturday morning, May 6th, Edward broke up his camp at Tredington and advanced to attack his foes.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

Bennett, in his History of Tewkesbury, p. 38, says that he marched along the Rudgeway, crossed the Swillgate2, by Prest Bridge, and occupied the ground to the southward called the Red Piece.

Note 2. Leland says: "Ther is a litle broke caullid Suliet cumming downe from Clive, and enterith into Avon at Holme Castelle by the lifte ripe of it. This at sodayn raynes is a very wylde brooke, and is fedde with water faulling from the hilles therby." Itin. vi., q.n., ed. 1709.

But it would have been a rash proceeding to attempt the crossing of a deep brook where it was spanned merely by a little wooden foot-bridge within a quarter of a mile of the enemy's front. More probably he crossed the Swillbrook at Tredington, where there appears to have been a bridge from early times, and made Tredington and Hoo Lane, along which runs the municipal boundary of Tewkesbury, his base of operation.

As the chronicler tells us, Edward "apparailed hymselfe, and all his hoost set in good array; ordeined three wards, displayed his bannars; dyd blowe up the trompets; commytted his caws and qwarell to Almyghty God, to owr most blessed lady His Mothar, Vyrgyn Mary, the glorious Martyr Seint George and all the Saynts, and avaunced, directly upon his enemyes."

The vaward, or van, was "in the rule" of Richard Duke of Gloucester, brother of the King, at that time only nineteen years of age, but already a skilled and brave leader. Edward in person and his younger brother, George Duke of Clarence, commanded the centre, and Thomas Gray, Marquis of Dorset, stepson of the King, and William Lord Hastings, who had fought bravely for Edward at Towton and Barnet, were in charge of the rear.

The King scems to have taken up his position about half a mile south of Gupshill, on the site of the drive to "Southwick Park" from the present highway. He had on his left a hillock, and in front of him a large field or close now called the Red Piece. The chronicler says that "whan the Kynge was comyn afore theyr fielde, or he set upon them, he consydered that, upon the right hand of theyr field there was a parke, and therein moche wood, and he thinkynge to purvey a remedye in caace his sayd enemyes had layed any bushement in that wood, of horsemen he chose out of his fellashyppe ijc speres,. and set them in a plomp, togethars, nere a qwartar of a myle from the fielde, gyvenge them charge to have good eye upon that cornar of the woode, if caas that eny nede were, and to put them in devowre and if they saw none suche, as they thowght most behovfull for tyme and space, to employ themselfe in the best wyse as they cowlde."

Somerset's neglect in failing to occupy Tewkesbury Park1 was a proof of his bad generalship, and hastened the disaster which he invited by his subsequent conduct.

Note 1. Leland speaks of the Parke of Theokesbyri as standing on the left bank of Severn. "The maner-place, he says, in Theokesbyri Park with the Parke was lette by Henry VII. to the Abbot of Theokesbyri." "There is a parke bytwixt the old plotte of Holme Castle and Deerhurst but it longgid to Holme, the Erles of Glocesters house, and not to it (Deerhurst)." He also says, "Ther is a fair maner-place of tymbre and stone yn this Theokesbyri Parke, wher the Lord Edward Spensar lay, and late my Lady Mary." See Leland and Leland, vi. 73, ed, 1769.

Barrett overlooks the statement of the chronicler that "the parke" was on the Lancastrian right, and places it on their left. The ambush he lays in Queen Margaret's Camp itself1?

Note 1. Barrett's Battlefields of England, p. 206.

It would appear that soon after the destruction of Holme Castle, early in the fourteenth century, the Earls of Gloucester constructed for their own use a manor-house in their park on a delightful eminence looking down on the Lower Lode. In the seventeenth century this was the property of the Pophams, and they and their descendants possessed it until early in the nineteenth century.

The battle began with an exchange of gunshot and arrows. The Lancastrians, owing to the loss of part of their artillery on the march from Gloucester to Tewkesbury, seem to have suffered some losses; but all might have gone well but for the rashness and impetuosity of Somerset. The chronicler tells us that he "knyghtly and manly avaunsyd hymselfe with his fellowshipe somewhat asyde-hand the Kyngs vawarde, and, by certayne pathes and wayes therefore afore purveyed, and to the Kyng's party unknowne, he departed out of the field, passyd a lane1, and came into a fayre place or cloos even afore the Kynge where he was embatteled, and from the hill that was in that one of the closes, he set right fiercely upon th' end of the Kyng's battayle."

Note 1. Probably the green lane between the lodge of Southwick Park and Lincoln Green.

Holinshed, who uses our chronicler freely, is responsible for the statement repeated by all writers on the battle that the Duke of Gloucester, unable to force the Lancastrian lines or come to hand-to-hand blows with them, made a feint of retreat in order to tempt Somerset from his strong position1, and that the Duke fell into the trap; but the words "therefore afore purveyed" would seem to suggest that this flank attack of Somerset on the Yorkists was part of a strategical movement carefully thought out beforehand. In any case it proved to be a very disastrous one, for the King appears to have crossed the brook which I have called the Coln and, supported by Gloucester, to have attacked Somerset in the close at the foot of the hillock, defeated him, and driven him in disorder up towards his original position.

Note 1. See Habington in Kennet, i., 452.

Between Gupshill and Southwick there is a deep depression of the ground which is exactly described by the chronicler, who certainly must have been an eye-witness.

In the meanwhile the two hundred spearmen, seeing no sign of a Lancastrian ambuscade in the park, and hearing the sounds of martial strife, hastened to the support of their King and attacked Somerset in flank. K

Having already more than they could do to resist the onslaught of the King and Gloucester, and not knowing what might be the strength of the new assailants, the Lancastrians "were gretly dismaied and abasshed and so toke to flyght into the parke and into the medowe that was nere, and into lanes and dykes where they best hopyd to escape the dangar; of whom netheles many were distressed, taken and slayne."

This plainly shows us that the fugitives who were slain in the "Bloody Meadow," in their attempt to reach the Lower Lode and escape into Malvern Chase, belonged to the right wing of the Lancastrian army under Somerset. Probably the left wing of the Yorkists was employed in completing their rout.

Some of those who have written on the battle tell us that when Somerset re-entered the Lancastrian lines somewhere near Gupshill, he upbraided Lord Wenlock who was conjointly in command of the centre for his inactivity and cowardice in failing to come to his help in the Red Piece1; and that he dashed out his brains with his battle-axe2.

Note 1. Nos. 34 and 40 on the tithe map are called Far Red Close and Red Close.

Note 2. Habington in Kennet, 1., 452.

During the commotion caused by this fatal act of violence King Edward, accompanied by Gloucester, forced his way into the entrenchments and attacked the young Prince and quickly put him and his following to discomfiture and flight. These being cut off from the Severn by the Yorkist left, succeeded, many of them, in crossing the Swillbrook and reaching the Ham, but they were overtaken by their pursuer near the Abbey Mill and were either slain with the sword or drowned in the mill dam. Then the victorious King would seem to have attacked the Lancastrian left, and finding them disheartened and in confusion, easily drove them through the Gastons, down the Vineyards, past the ruins of Holme Castle, into the town.

Amongst the leaders who were slain on the field were the Earl of Devon, Lord John Beaufort, Lord Wenlock, Sir John Delves, Sir Edmund Havarde, Sir William Yarmouth, Sir John Lukenor, Sir William Rous, Sir Thomas Seymour, Sir John Urman, Sir William Vaux, Sir (?) William Whittingham, and the following squires :—Henry Barrow, William Fielding, and Thomas Harvey, Recorder of Bristol. In an account of the battle drawn up apparently by the King's command and sent to Charles the Bold (now preserved in the public library at Ghent) several of these are omitted, whilst additional names appear as slain on the field1. The total number is said to have been one thousand.

Note 1. See Leland's "Itinerary," B. and G. Arch. Soc. Trans., xiv. 275, "Nomina occisorum in bello Gastiensi prope Theokesbyri." i.e. "Names of those killed at the battle of Gaston near Tewskebury".

The outline drawings of the battle of Tewkesbury and the execution of Somerset have been reproduced from Archaeologia, vol. xxi. by the kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries. They were copied from illuminated miniatures in the fifteenth-century Ghent MS.

See Archaeologia Volume 21 Section III for the drawings.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

The Duke of Somerset, the Prior of St. John, and many others who had escaped from the battlefield, sought the protection of Abbot Streynsham in the abbey church, whither, Leland tells us, they were followed by the King with drawn sword; but a priest, holding aloft the Host, forbad his defiling the sacred edifice with blood1.

Note 1. See Warkworth's Chronicle, Camden Soc., p. 18.

Our chronicler tells us that "the Kynge toke the right way to th' abbey there, to gyve unto Almyty God lawde and thanke for the vyctorye, that, of His mercy, He had that day grauntyd and gyven unto hym; where he was receyvyd with procession, and so convayed thrwghe the Churche, and the qwere, to the hy awtere, with grete devocion praysenge God and yeldynge unto Hym convenient lawde. And when there were fledd into the sayd churche many of his rebels in great nombar ... or moo, hopynge there to have bene relevyd and savyd from bodyly harme, he gave them all his fre pardon albe it there ne was, ne had not at any tyme bene grauntyd any fraunchise to that place for any offendars .agaynst theyr prince havynge recowrse thethar." If the abbey had been granted the right of sanctuary, the right did not cover the crime of treason. Our chronicler, moreover, says that Edward granted permission to the servants and friends of Prince Edward to bury him and the others slain ‘with him in the battlefield in the abbey church, or wheresoever they pleased, "without any qwarteryng or defoulyng their bodies by settying upe at any opne place."

A day or two later, however, the Ghent manuscript says on the 6th (Warkworth says on Monday), such of the leaders as were found in the abbey or in the houses of the citizens were brought before a court-martial consisting of the Duke of Gloucester, Constable of England, and the Duke of Norfolk, Marshal of England, and, being found.guilty of treason, were sentenced to be beheaded. This sentence was carried out at the Cross, but the bodies were not dismembered or exposed on the gates of the town or elsewhere, but were allowed honourable burial.

The names of those who thus perished by the executioner's axe were the Duke of Somerset, Sir Humfrey Handeley, Audley or Hadley, the Prior of St. John, Sir Gervase Clifton, Sir William Cary, Sir Henry Ross, Sir Thomas Tresham, Sir William Newburgh, and many gentlemen of good family and position. Leland adds that the King spared the lives of Sir John Fortescue, Chief Justice of England, Doctor Mackerell, John Throckmorton, Baynton, Wroughton and others. Sir William Grimsby also was pardoned. Sir Hugh Courteney appears to have been captured later on and beheaded.

The slaughter of the fugitive Lancastrians did not, however, cease with the battle, or with the execution of the leaders at Tewkesbury Cross.

The Register of John Carpenter, Bishop of Worcester, shows that several churches and churchyards in his diocese were desecrated at this time by blood-shedding, and had to be "reconciled." The abbey church of Tewkesbury was re-dedicated on account of its pollution with the sword after the battle—a fact which militates against the truth of the statement that Edward gave those who had taken refuge there free pardon.

At Didbrook, near Winchcomb, several Lancastrians were ruthlessly put to death in cold blood within the sacred walls of the parish chureh, and so horrible did this sacrilege appear to the rector, William Wytchurch, Abbot of Hayles, that he rebuilt the church at his own expense1.

Note 1. In the east window of the chancel are the remains of the following inscription: "Orate pro a'i'a Wyll'ii Wytchyrche qvi hoc tem= plum fundavit cum cancello." i.e. "Pray for the soul of William Witchurch, who founded this church with its chancel".

Our chronicler tells us that on the 7th of May, when the executions of the Lancastrian leaders had taken place, Edward IV left Tewkesbury for Worcester, and on the way news was brought to him that Queen Margaret had been found not far from where he was in "a powre religiows place", where she had hidden herself for safety early on Saturday morning after Prince Edward had taken up his position in the line of battle. Tradition says that the Queen crossed the Lower Lode and awaited the result of the battle at a house on the road from Tewkesbury to Bushley called Payne's Place.

The Rev. E. R. Dowdeswell, President of this Society in 1902, writing in 1877, says: "The Queen's room is still to be seen in Payne's Place in which Queen Margaret slept after the disastrous day at Tewkesbury1" On the day following the battle, Sunday, May 5th, when all the terrible details of the Lancastrian defeat had been told her, she fled, perhaps to Little Malvern Priory, under the shadow of the Hereford Beacon, or it may be to some "powrer religiows place" which has long since been destroyed and forgotten. Two days later Edward was assured that "she shud be at his commaundment", and by his orders Sir Willlam Stanley conducted the bereaved Queen to him at Coventry, where he tarried from the 12th to the 16th of May2.

Note 1. Barett, Almanack and Year Book for 1877.

Note 2. Warkworth tells us that the following ladies were also taken prisoners: The young wife of Prince Edward, the Countess of Devon, and Dame Kateryne Vaux.

On the 21st she [Queen Margaret] was compelled to grace the king's triumphal entry into London, and was then committed to the Tower, where her royal consort was a prisoner. Two days, some say a few hours later, it was told her that she was a widow as well as childless. She was detained a prisoner in different fortresses in England until November, 13th, 1475, when a ransom of fifty thousand pounds was paid by her father, and she returned to her old home in France. On the 25th of August, 1480, she breathed her last in the Chateau of Dampierre, at the age of fifty-two.

All About History Books

The Chronicle of Geoffrey le Baker of Swinbroke. Baker was a secular clerk from Swinbroke, now Swinbrook, an Oxfordshire village two miles east of Burford. His Chronicle describes the events of the period 1303-1356: Gaveston, Bannockburn, Boroughbridge, the murder of King Edward II, the Scottish Wars, Sluys, Crécy, the Black Death, Winchelsea and Poitiers. To quote Herbert Bruce 'it possesses a vigorous and characteristic style, and its value for particular events between 1303 and 1356 has been recognised by its editor and by subsequent writers'. The book provides remarkable detail about the events it describes. Baker's text has been augmented with hundreds of notes, including extracts from other contemporary chronicles, such as the Annales Londonienses, Annales Paulini, Murimuth, Lanercost, Avesbury, Guisborough and Froissart to enrich the reader's understanding. The translation takes as its source the 'Chronicon Galfridi le Baker de Swynebroke' published in 1889, edited by Edward Maunde Thompson. Available at Amazon in eBook and Paperback.

[6th May 1471] With regard to most of the particulars I have given, there is little disagreement amongst the chroniclers; but the same cannot be said of what they tell us with regard to the fate of the young Prince Edward (deceased).

In this respect they are divided into two hostile camps. Those who had Lancastrian sympathies and wrote during the reigns of Henry VII. and Henry VIII declare that the unhappy Prince was murdered in cold blood as a prisoner; and Polydore Vergil, whose History was printed in 1534, does not hesitate to accuse Edward IV and his two brothers of the murder. The chroniclers who were contemporary with Edward IV and Richard III declare that Prince Edward was slain on the field of battle. The commonly received account is that he was taken prisoner by Sir Richard Crofts; and on the King issuing a proclamation that the person who produced him should receive a pension of £100, and that the Prince's life should be spared, hie was brought into the royal presence. Then followed the scene which Shakespeare has immortalized: The King having. haughtily inquired how he dared invade his dominions and stir up his subjects to rebellion was as haughtily answered by the lad that he came to rescue a father from prison, and regain a crown which had been usurped, whereupon the King struck him with his gauntlet, and Gloucester, Clarence, Dorset, and Hastings hurried him away from the King's presence and despatched him with their poignards.

Local tradition, which probably owes its existence to these Tudor chroniclers, points out a shop in High Street near the Tolsey where the cruel deed was done; but it is more likely that the King occupied the beautiful house at the Cross restored by the late Mr, Tom Collins.

On the other hand, our chronicler says, "In the wynnynge of the fielde such as abode hand-stroks were slayne incontinent; Edward called Prince, was taken, fleinge to the townewards, and slayne in the field."

Warkworth says: "And ther was slayne in the fielde Prynce Edward, whiche cryede for socoure to his brother-in-lawe, the Duke of Clarence.”

De Commines says: "And the Prince of Wales, several other great lords, and a great number of common soldiers were killed on the spot."

Leland, writing as late as 1540, says: "Edwardus Princeps venit cum exercitu ad Theokesbyri et intravit campum nomine Gastum . . ibl occisus.”

The body of the young prince is said to have been buried in the choir, and an inscription written by the Rev. Robert Knight, vicar of Tewkesbury, was engraved on a brass plate:

Lest the memory of Edward, Prince of Wales, cruelly slain after the memorable battle fought in the nearby fields, should entirely perish, the devotion of Tewkesbury caused this commemorative plaque to be placed, in the Year of Our Lord 1797.

"Ne tota pereat memoria Edwardi Principis Walliae, post prelium memorabile in vicinis arvis depugnatum crudeliter occisi; hanc tabulam honorariam deponi curavit pietas Tewksburiensis, Anno Domini, MDCCXCVIL."

![]() Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

Become a Member via our 'Buy Me a Coffee' page to read complete text.

What became of this I know not, but at the present time the following inscription, written by my old friend the late Mr. J. D. T. Niblett, marks the supposed site of the Prince's grave:

Edward, Prince of Wales, slain at Tewkesbury, 1471. Here lies Edward, Prince of Wales, cruelly killed while still a youth, in the year of our Lord 1471, on the fourth day of May. Alas, the fury of men! You are your mother's only light, and the last hope of her people.

"Edward Prince of Wales slain at Tewkesbury, 1471. Hic jacet Edwardus princeps Walliae crudeliter interfectus dum adhuc juvenis Anno Domini 1471, mense maii die quarto. Eheu hominum furor. Matris tu sola lux es, et gregis ultima spes."

With regard to the Lancastrian leaders: Somerset, his brother John, the Earl of Devon, and Sir Humphry Audley were buried before the image of St. James, near the altar of St. Mary Magdalen; Sir Edmund Havarde, Sir William Wittingham, and Sir John Leukenor were buried in St. John's Chapel; Sir William Vaux was buried before an image of Our Lady on the north side; Sir John Tresham was buried between the altars of St. James and St. Nicholas, and many others were laid in the churchyard1.

Note 1. I would acknowledge my indebtedness to an able paper on the battle of Tewkesbury in Richard Brooke's Visits to Fields of Battle in England, 1857.

I also have to thank Mr. F. W. Godfrey, junior, for the photographs of Gupshill Farm and for much kind help in my frequent examinations of the battlefield.